Two words – coined into one – have taken tourism authorities of the Department of Tourism (DOT-CAR) to time’s luminosity, associating these with the existing, natural wonder of highland Cordillera Administrative Region (CAR). Words called “eco-tourism.”

Like in any classroom, eco-tourism can be subdivided and studied as many subjects, from trees, plants, settings, avian, insects, the land, the people, the way of planting, the way of life, tattooing, among others.

Those traversing highland roads for the first time, travel, then be invited gladly to typical farming families nestled among forests in rural agricultural settings in highland Cordillera particularly along the belt of Halsema National Highway, after a storm had presaged passing.

It’s a traveler’s providence passing through such trail, once in a lifetime’s beckon.

But for highlanders already experienced in such farming life, lucky they are, for once, in a passing of life’s adventure, they have connected with the land in the trails through time, finding contentment in an evening saunter through the woods and muddy paths, albeit with problems.

One day in the lives of typical, rural, highland farming families may not particularly be inspiring to city dwellers. But it offers a rare glimpse of different cultural perspective of how they connected with the land in a mythopoetic way and how urban dwellers and tourism planners merely see it as outdoor recreation, eco-tourism, tourist destination or sustainable tourism.

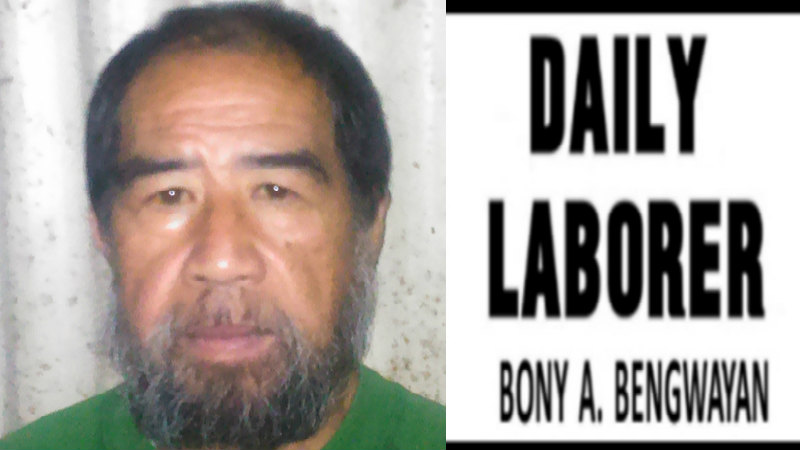

For those who have never tasted of, say, highland farming, are searching for deeper relationship with the natural world than that provided with conventional opportunities like outdoor recreation or eco-tourism, well, come along with Daily Laborer to track some families relate stories and explain their feelings in connection to living with the land and their values attached to their concepts.

Before the crack of dawn, the mother of any farming family is up and about, preparing for morning meal. Nowadays, all farming families are modern. But they still keep intact the hearth. For the winds at Halsema National Highway can often be brutally chilly in the morning.

Using hearth, is where the magic begins. As one watches the small fire lapping heartily to cook the morning meal, one can go out of the house where the hearth is, and finds the smoke lazily curling towards the sky, sending cryptic messages to the clouds.

While the mountains enveloping farming communities try to clutch at the receding night shadows trying to retreat to welcome dawn’s coming.

In a typical highland, farming home – after morning has broken – you discover to your delight farmers already have had early breakfast (they feed visitors heartily) and ready head to the hills where farm plots have been battered by the rains and need to be hoed again.

Take Moises Aiben, planter at Cada, in Mankayan, Benguet. After having scanned last Saturday the sky and found it fine to his satisfaction, he said, “Ay! Na-ay ay maiwed et di udan, ta entaku mamuknag. Nasayaat din Apo!” (Yes! The rains have gone. Let’s go back to work. God is good!”

And farmers will gladly invite you to go with them and discover the beauty of holding a “gabion,” (hoe), a sickle, a spade or “sanggap” (garden trowel).

Highland farmers (Nowadays, many are educated in BS in Forestry, BS in Agriculture, BS in Agricultural Engineering, Nursery Management, horticulture, etc.; most schooled at Benguet State University (BSU) teachings can pique anyone’s interest. It’s never enough for them to engage beginners in scholarly discussions about connections between land and people.

No. Apparently most of their teachings involve some kind of experience in the out-of-doors. To get a grade of 80 and above from them, you have to strap on a pack and wade through the muck. Along cold trails, you put on that bonnet, bend into the wind and blow hot breath onto your chilly fingers.

You have to burn your soggy socks by a roaring fire, hear stories punctuated by song of the hooting owl or the whispering lullaby of Benguet pine trees as they let go their needles to the ground.

For highland farmers are dammed, good “professors” when it comes to teaching the uninitiated, the ways of the land and the people.

After hearing these farmer-teachers, you will find to your delight doing unintelligible scrawls on your notebook or on the back of a piece of already used paper, with parenthetical insertions stuffed between lines. Obscure citations. Anecdotes. Trip notes. Poems. Song lyrics. Enviro-music. Eco-philosophy. Whatever comes to mind.

By whatever topic, these farmer-teachers’ messages always return sooner or later to the same observational or pragmatic: if you want to learn something about anything, you need to immerse yourself in it. You need to experience your subject fully.

You need to cook your food over an open fire and if no vegetables are around, learn to cook and eat the dandelions growing profusely on Cordillera hills. A good vegetable as any can be.

And if you’re wanting to learn happens to be highland environmentalism, you need to get out of your comfort and on the land, preferably under your own steam and certainly, away from urbanity.

You have to prove that there’s a whale of a difference between an arm-chair environmentalist and the On-the-Job Training (OJT) environmentalist.

When it comes to making sacrifices, none is more familiar than highland farmers particularly when there’s crop failure and low prices, often discouraging. But one thing they won’t trade: their sunny, indigenous disposition.

In seconding thoughts of Aiben on God being good and going back to work, Bentley Alpiso, farmer at Bahong, La Trinidad, Benguet, and wishing someday to get married, said heartily in Ibaloy,” Man-eyyannak emo, shim Bahong, shiman day nak pangardenan din sabong, Ta nu kultahen sha, E-ilaw shed Manila, panpififingilan sha, ta gwaray kwarta ilako si Elf, (he referred to a flatbed half-truck generally preferred by farmers) ta nu ayshe Elf, ayshe kasar.”

(I’ll stay in Bahong, La Trinidad, there where I will raise flowers. That if you send it to Manila, they will line up to buy them. So, I will have money to buy Elf. Because if there is no Elf, there is no marriage.)

There’s this indigenous joke around Cordillera camp trails that if a man has no Elf, chances are, prospects of marrying get dim. A humor of belongingness – a humor to strive better.

In Buguias, Benguet, Ferdilita Lumis-a, owner of a vegetable stall along the highway was asked last Saturday by Virgelyn Tobias, from the lowlands, and first-time visitor in the highlands, if the Elf story was, indeed, true.

Ferdilita smiled patiently at Virgelyn and with condescending smile, explained, “Blessed are we who can laugh at ourselves for we shall never cease to be amused.” Shades of indigenous belongness.

To pass Cordillera paths less travelled by, is to be part of “keepers of the trail,” to experience a spirit of belonging, to have an intelligence, a native or natural intelligence, intelligence not for abstract ideas, but for a place, a big place like CAR.

Daily Laborer, likes to believe that a native is a human, creature or plant indigenous to a given geographical area, a space boundaried and defined by mountains, rivers or coastline and not by latitude, longitude, with its own peculiar mixture of weeds, trees, bugs, birds, flowers, streams, hills, rocks and critters (including people), its own nuances of rain, wind and seasonal change.

Native intelligence develops through an unspoken or soft-spoken relationship with these interwoven things. It evolves as the native evolves in his/her region.

A non-native traveller might awake in the morning in an environment and feeling nothing at all; A native wakes in the morning in a cosmos, senses the imperceptible shifting, migrations, moods and machinations around. Like the growing green things, the earth, the sky.

And in experiencing being part of “keepers of the trail,” first time Cordillera travellers will find for themselves they aren’t sold to the idea that one gets native intelligence just by wanting it. But rather, through long intimacy with a certain native world, one begins to catch it, kind of like catching a cold.

It’s a cold worth catching. Unlike the cold associated with the pandemic.