Although almost fading, a couple of pictures of his home village are among Marciano Guillao’s prized possessions. The photos are among the few documentary evidence of his home village, whose fresh springs teeming with eel and freshwater fish, and verdant forests with various birds he still vividly remembers.

But those images of his home village that he has treasured for over 30 summers, he laments, are gone. The pictures taken in the 1980s, which showed his mother against a backdrop of golden rice fields heavy with ready-to-harvest grains, were replaced recently by a different landscape altogether – inner bowels of the earth literally turned upside down.

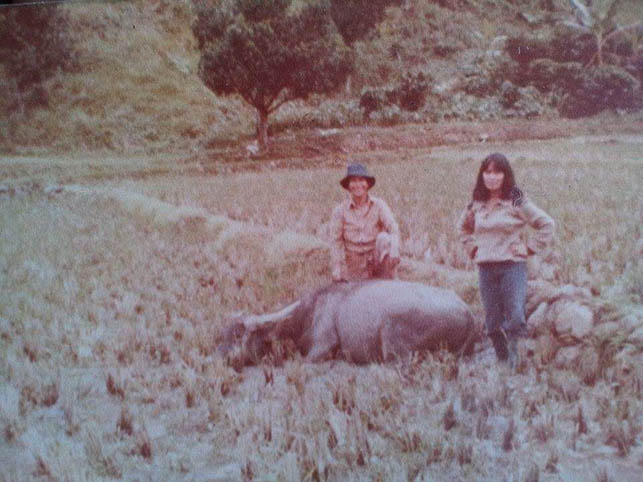

Photo 1: When the land provided in abundance

“Now, I see an ailing landscape that can never be healed”, laments the over 50-year old Marciano.

The old picture in Marciano’s archive showed that above and around the rice fields was a green lush of secondary and old-growth forests. Although the village was once logged in the 1960s and1970s, new trees had regenerated, serving as the watershed and headwaters of a vital river and springs, which have irrigated the fields and supplied potable water for Guillao’s family for decades.

The rice field, which the pictures captured, was in Tayab, a remote sub-village of Runruno, one of the villages of Quezon town in Nueva Vizcaya province. Runruno, which means abounding in tall grass reeds, was eventually settled in the early 1960s, promising abundance to the early settlers who engaged in upland farming and later, gold-panning and small-scale mining.

Once a peaceful settlement, whose peace and quiet was occasionally disturbed by some noisy drunk men, Runruno has become a flash point recently after a big UK-based company set its eyes on the village’s minerals.

Tayab was the first settlement in what was to be known as Runruno barangay (village). The first settler, as Marciano recalled, was Bucaycay Guillao, his uncle.

Bucaycay was originally from the village of Sagpat in Kibungan town, Benguet province.

The part of Runruno that Bucaycay explored was so isolated one had to walk for almost a day to reach the place. But Bucaycay saw promised abundance for a pioneering family’s wellbeing in the verdant thick forests, the sloping hills, the river and springs.

Inspired by the stories of Bucaycay, his brother, Camilo, followed suit. After visiting the place between 1964 to1969, Camilo finally found a spot to farm in what was called Lintongan, which a long-time friend offered.

In no time, Camilo established a farm, planting camote or sweet potato, rice, pineapple, banana, and various fruit trees. Near a place called Malilibeg, he allotted this to “traditional mining.”

To extract gold ore, he used crude tools — shovel, pick, sledgehammer and a wheel borrow.

In 1970, Camilo returned to Sagpat, Kibungan to usher in his family to finally settle with him in Lintongan.

After a year of hard work in Lintongan, Camilo’s family acquired a three-hectare thickly-forested land in Tayab near the Sulong River. Mario Bani, a Kalanguya resident, sold the land to Camilo. The Bani family had long been a steward of the place for years.

Camilo developed a hectare of his land as irrigated rice field. Another hectare became vegetable plots, some 500 square meters was for the family’s house, and the rest for foot trails, grazing land and orchard.

Before he acquired the land, Camilo already saw its potential in supporting his family. The area had a spring with potable water. Nearby was a river, which would irrigate the newly established rice field.

From the mountain near the family’s home, the family could hunt wild game like fowls and wild boars. Below the spring was about a100-square-meter natural fishpond where the family could catch fish and shells.

Photo 3: Pond no more

The family’s home overlooks the 15-meter wide Sulong River across the main road where the family and friends would frolic and swim during summer. Food for family picnics was no problem as edible ferns were aplenty along the river banks as well as wild berries.

The river also abounded in fresh water fish locally called wadingan and bunog, crabs and frogs beside introduced species like tilapia and dalag, says JoAnn, citing recollections from her father, Marciano.

The Guillao family, however, noted some drastic changes in the late 1970s. The temperature became warmer and, warmer so much so that the river decreased by a third of its original size.

“The river became a creek,” says Marciano.

Despite the changes, the Guillao family continued with their upland farming and supplemented this with small-scale mining.

Through the years the village economy became vibrant as the Guillao family and other migrant settlers that followed engaged in both farming and small-scale mining. Other livelihoods, like petty businesses, soon emerged. More stores were put up and the retailing business flourished as well. Benefits from the local economy then were dispersed for almost everybody.

But all these have changed and life in the village is far different since the entry of large-scale mining.