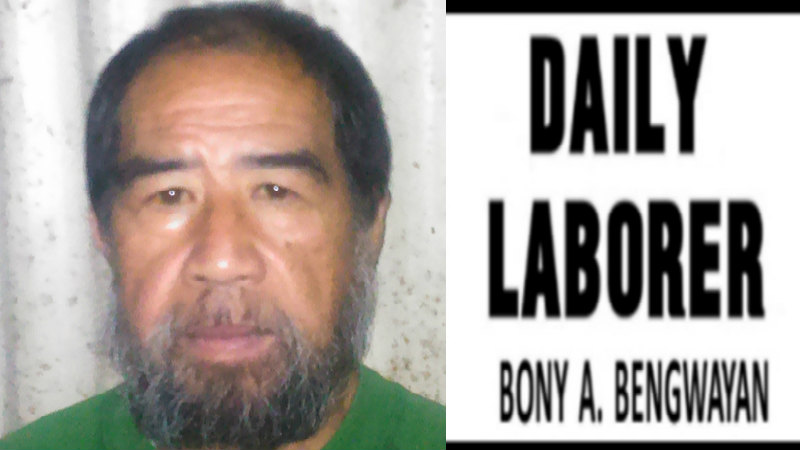

This trabahador, who couldn’t accomplish any work assigned to him, decided last Sunday to visit the graves of his father, Bony, Sr., and his younger soldier-brother, Jeffrey, who both lie peacefully at Lubas Cemetery, in La Trinidad, Benguet.

He intended to at least light candles on the tombs of his long gone father and brother who are now happily yodeling together in the Happiest Grounds in the sky, a blissful wonderland perfectly created only by the Almightiest of Creators, and known by us mere mortals by the spelling, G-o-d.

As his thoughts settled on memory of his father and brother, the trabahador wondered whether the two, up in the sky, were presently gazing down at him, his brother Jeffrey nudging the ribs of their father and saying, “Dad, kitaem kadi ni Manong, uray tatta a lak-lakayanen, madi na pay laeng ammu ti agbarbas. Kasanu maayatan dagiti agbasbasa ti Herald Express nu maserpatan da ti letrato na idiay column na a Daily Laborer nga agruprupa isuna nga kasla goons. Ti salbag a pagano!”

Aws! He remembered too well his brother Jeffrey always sported a clean look which made girls look twice, thrice, many times his way, while his trabahador-manong never got even a pouting glance from any member of the fairer sex.

He, too, remembered his old man for his clean record as bus driver of the old Dangwa Bus Company. Many Cordilleran folks remember him as driving with steady hands and steel nerves.

Whenever the trabahador’s old man was assigned to ply the old Baguio – Bontoc route of Halsema National Highway which before was rugged and full of potholes (Halsema was then dubbed before the Abortion Road) and took seven hours or more to traverse, the old man completed the drive in less than seven hours.

Cordilleran folks and students before preferred riding in the old man’s assigned bus because he completed his driving route earlier than others. They would cue up to take the ride.

Do you still remember the jolly old driver of Dangwa Bus Company with the nickname “Dos-dos?” Well, the late Dos-dos (bless his soul) was known by Cordilleran riding folks as the “slowest driver” then in the company.

Whenever riding folks coming from Bontoc would urge Dos-dos to drive faster in going to Baguio, Dos-dos was famous of saying, “Saan met nga umalis didyay Baguio. Dumanon tayo tu idyay Baguio.” Or vice-versa. Those hurrying to Bontoc, Dos-dos would say, “Saan met nga pumanaw ti Bontoc. Madanon tayo yun tu ti Bontoc.”

Cordilleran riding folks would often compare the driving of Dos-dos and the trabahador’s father. Once, the trabahador was forced to ask his father why Dos-dos drove slower than him. And the trabahador’s father gently said, “Because, Son, Dos-dos is a better driver than me.”

The trabahador shook off the memories flooding him of his dad and brother. He got the bunch of flowers which his mother told him to bring to the cemetery, placed it in a paper bag, together with the candles and went to a store and purchased a lighter.

It was past 6: 0’clock PM when he reached Lubas Cemetery, an hour when daylight struggled to linger put but was slowly being pushed back by the incoming darkness, creeping to turn to night as the hours dragged on.

Or, to say, the least, it was already dusk, darkness gathering to fall and envelope the countryside.

Wending his way along the tombstones, the trabahador reached the graves of his father and brother.

Nearby the graves of his father and brother, the trabahador spotted a man, maybe in his fifties, sitting on one of the tombstones. The man was alone with a far-away look.

The man turned his gaze towards the trabahador who nodded at the man and said, “Good evening, apoh.” The man replied in return, in Ilokano, “Naimbag met a rabi-im,” in clear but somewhat gravelly and off-key voice.

It was that moment the trabahador noticed the man was well-dressed, in formal attire, with a coat and a tie. His hair was well-combed. Even in the gathering darkness, the trabahador saw the man’s black shoes were sparklingly shined. It was as if the man was going to attend a formal gathering.

Appraising the man, the trabahador was forced to murmur to himself, “Naks! Dayta a ti panagbado,” unlike himself who couldn’t even remember if he changed his underwear for a year.

Still, the trabahador couldn’t shake off a sense of eeriness and haunting feeling that seemed to pervade the air. . .

Op kors, the trabahador was very well aware of the embarrassing situation in which he was putting himself, when, in this present age of skepticism, he dares to write in all candor of belief and spirit, a conscious and straight from the horse’s mouth account of an apparition, a phantom, or as Cordillerans say, as “anito.”

A rascal, an imposter, a fool and visionary, these are probably the words this trabahador will be subjected to sneers of contempt or smiles of ridicule from readers.

With incredulity registered against this trabahador, readers will dismiss and rebuke him with the temperament of the readers, either with a petulant remark about an unlearned, uneducated and unschooled lunatic attempting to impose such unfounded superstition upon an enlightened public.

Or, with friendly and sober recommendation, jolly readers may as well tell this trabahador to have his hair and beard shaved, see a psychiatrist or physician and have his coconut examined with little delay as possible for expounding that spirits abound in this modern and hi-tech world.

Boisterous maybe the mirth which will be twitted, taunted and heaped on this trabahador for his unfounded conviction, he has no other sinister purposes to answer, no theory to establish but write with what he saw while in the full possession of his faculties.

That being the case, mi senor y senores, mi amigos y amigas, the trabahador is still thus determined not to suppress what he conscientiously believed to be what occurred, inconsistently happening with the ordinary course of human experience.

For, whether accepted or not, there still exist the universal belief in ghosts, in all ages and among all nations.

It’s said that ghosts never appear to more than one person at a time. Anyone there may discredit this, but can you really discredit the belief that humans have souls or spirit beings that separate from the clod of earth humans were made once death takes over?

Humans also believe that spirits of the dead are accounted for by the Maker. That being the case, spirits are real.

Do they appear to the living? You answer it. For this trabahador can’t.

For as he sensed and eerie and haunting feeling pervading the air while having said “Good evening, apoh,” to the unnamed and well-dressed stranger sitting on one of the tombs nearby where his dad and brother were buried, the stranger said, “Adda lighter mo, ta sindi-ak man daytoy sigarilyok,” while putting an unlighted cigarette between his lips.

It was at that time, the trabahador also saw a dog as it trotted near them, the hairs on its back bristling.

He turned his attention to the paper bag he dropped on the ground, rummaged through the flowers and candles in search of the lighter he bought to light the candles. For some moments he couldn’t’ find it and then, aha! He found it.

He got the lighter out of the paper bag, turned around to give it to the well-dressed man – but the man sitting on the tomb was GONE. He VANISHED into thin air.

Scratching his head, the laborer tried to recover from his surprise, endeavored to persuade himself he was deluded by some hocus-pocus of the mind or deception of the visual organ.

But in either case, the trabahador could not account for the terror of the dog that came to the cemetery as it howled mysteriously and hauntingly with sadness in the direction where the man previously sat.

He placed the flowers before the graves of his dad and brother, lighted candles and reflected on Undas. He wondered if the day, Undas, was meant to be gay or sad, for if you reverse the word Undas, it is sadnu!