Baguio City—Hurl derogatory remarks at them. Include a dirty kitchen sink. But quit, they won’t.

Two words often spouted daily in Cordillera Administrative Region (CASR) and Region 1 seem to have become worn out by tongue use, yet simply describe men and women who, today, face a tough, uphill fight against a surging disease in this country battling on more than just one war zone.

“Frontliners,” they are merely described.

They appear in persons who don the well-familiar white garments of a nurse or traditional white coat of a doctor. They report for duty in dress uniform of a medical technologist or other allied health professionals.

They punch in their cards for work, clad in official regulation apparels of various government offices and line agencies.

They stand erect in official camouflage uniforms of the Philippine National Police (PNP) and the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP).

They beat morning rush not to get late, in formally required vestments for government and private banks, food establishments, groceries, malls, department stores, logistic drivers, delivery services and members of the private sector.

Or they work in different working clothes for civil society organizations performing charity work.

All – frontliners – face a challenge they never faced before: hold the Philippine health’s ramparts steady even as their thin line threatens to buckle under the brunt of a war launched by a formidable foe.

Presently, the Philippines grapples with surging cases, and expert analysis point it makes it Southeast Asia’s latest corona epicenter this week. The medical sector, also notes things won’t be getting better anytime soon; the fight seems to get drawn-out.

Frontliners know this fact better than most Filipinos do. Exhausted to the limit, they may opt for a leave (if granted) as breather, but quitting, as an option, has never crossed the minds of most.

CAR/ Region 1 frontliners deem quitting in midst of the fight as an excuse of the most expensive brand of self-defeat they could ever face in their lives. They’d rather exude hope.

Such optimism flows from the bosom of Joy Bing-iyan Bongotan, government nurse assigned at Baguio General Hospital and Medical Center (BGHMC), after Herald Express’s interview last Monday.

Joy said: “During the almost 6 months’ hiatus of battling covid-19, I was one of the people in the frontlines being pushed to my limits. I like that I can save lives. There’s this joy it brings me.”

Joy took oath to take care of people. But it’s more an oath to Joy of taking care of the sick. For while she may not be able to help everyone, even in a nurse’s lifetime, she can at least, save somebody to continue breathing, as she fervently stated, “Every day, I go out there to save at least a life, or contribute to the saving of a life.”

See other columns:

Many fear this present an unpredictable bind unleashed by an unseen foe. Unseen by most Cordillerans, lowlanders and other Filipinos is a “cause, greater than thyself,” of frontliners often spent, frustrated and terrified.

Joy revealed a glimpse of their hidden emotions when she narrated, “Every job is challenging; it breaks and makes you. But as a nurse, standing for hours during a shift, holding your urge to urinate while using an adult diaper, holding back your tears when you lose a patient, having to work in a short-staffed shift and so many other things I can’t put to words.”

“I know death, seen loss of life, witnessed sufferings many times. But at least I can say, did all my best for my patients . . .,” Joy reluctantly divulged.

Tackling this threat took a sense of urgency on part of health frontliners more susceptible to an exposure they’re trying to snuff out as their fear becomes more palpable as days turn to nights.

Where, before, they started work lively; presently, uncertainty stalks that liveliness like eerie burden. Joy noted: “The job remains the same, but since the pandemic started, I have to take extra care of myself, too, to limit transmission. I have special gear to wear before entering a patient’s room – mask, gloves, gown, googles. I dress up and undress every time we come in and come off. It takes time; it’s hot and tiring. It’s like you’re in a sauna suit.”

Corona has stripped a chance for both patient and nurse building a bond, if for a while at the hospital, as Joy said, “With PPE (Personal Protective Equipment), relational aspect is different than before. It’s not easy to build a connection with the patient because they don’t recognize you, hidden behind mask and googles.”

It’s a brutal time for health workers in the country. Not that it wasn’t before. Despite such snag, they appreciate patients humoring them. And Joy remembers patients telling “they look like astronauts.” In response, Joy humors back, saying, “Come, join us to Mars, kasi ayaw na namin sa Earth!”

One can only guess what disquiet runs through a frontliner’s mind. Nonetheless, hearts of many residents reach out to them as mark of respect to a Herculean effort. And Joy wants these kind-hearted souls to know frontliners’ feelings: “One of the rare good things about this situation has been the generosity of people, the locals, patients, families, restaurants, bakeries who continued to give us food. I feel, we feel, appreciated and we are grateful for it!”

It’s said a crisis can be a catalyst in uniting an action. Apparently, some prefer to do contrarily. As Joy lamented of the time, “she was inside the BGHMC covid ward, getting vital signs of one covid suspect, her sweat dripping to the floor,” (she was in PPE for more than 6 hours) and the suspect’s watcher told her rudely, “Kayo nagbigay ng virus sa amin, kaya nagtatagal kami ditto.” (in the hospital).

Hearing such insolence, Joy felt the PPE heat doubled, turned to the watcher who was big and instead of arguing, said, “Paki-ayos na lang ang inyong face mask, sir, hindi po ang baba ang naka-face mask.”

Exiting the patient’s room, Joy mumbled to herself, “Narigat nga maki-apa ti dakkel nga tao nga battit ti utek na!”

Much as she wanted to tell that watcher how demeaning his statement and had no right uttering such, she calmed down, rightly calculated, she’d be “wrong in the eyes of many.”

There was time she was in a grocery and people in queue. The cashier beckoned her forward instead; she obliged. But overheard one customer who sarcastically commented, “Frontliner gamin ya, isunga.” Joy kept her peace, paid and hastily exited out of the grocery.

Of that experience, “Sometimes, instead of being proud as a frontliner, I feel ashamed, the looks that people give to us. . . like walking virus, etc…,” Joy reflected.

For the ups and downs corona brought, Joy lingers her thoughts for the Baguio City Police Office, (BCPO). She remembered that time, a police officer of BCPO offered her a ride as she strode from work. Although unable to secure the number of the BCPO station, the mobile car and the unnamed officer, Joy says, “Sir, matago, tago ka!” (May you live long, Sir).

Such deep statement applies to all unidentified BCPO police officers, silently doing the rounds in keeping frontliners safe and sound.

See more features:

People of Sagada, Mountain Province, where Joy hails from are surely proud that one of their daughters is part of the entwining strands strengthening the thin frontliners line.

Another government nurse, Myia B. Mendez, also with BGMC gave her insight on how men and women behind the mask are mere human beings trying to surmount odds by betting their lives on the line but susceptible to hidden fears.

Myia said, “I feel proud, knowing I’m helping our country this pandemic and part of the fight. But as a nurse handling patients, I’m also scared, not for myself but for my family, knowing we can’t see covid, we don’t know who has the covid unless tested/swabbed.”

Yet, in trying to help, Myia, like many frontliners, experienced the jeopardy of those who eschew misguided fears that health workers carry corona.

There was, “one time, around April,” Myia narrated, “when we were still in Enhanced Community Quarantine. I went to a store in our neighborhood and they asked me about the current situation of the covid cases in the hospital (BGHMC) where I am currently working.”

Myia assured her neighbors they “don’t need to worry because we are using PPE’s and are also very careful in handling patients. But the look in their faces – are still in doubt – and I felt they didn’t want me in their place.”

less is known by many how frontliners take on the job daily. But it can be measured by their effort of whenever doubt seeps in them on how far they’d go, they reflect on how far they have arrived at this point in time, in the company of colleagues, patients and friends.

Myia summed it: “Sometimes, we do really feel burned-out, especially that we are working 12 hours in a shift. But smiles and thank you messages from our patients also serve as a reminder that we are doing a great job and shouldn’t give up.”

For Myia believes frontliners must punch through this obstacle for normalcy to trickle back: “I always see things in a positive way, always hope that this will all end soon and we all go back to normal again. I am also thankful for my colleagues. We always help each other, which always makes our work easier and lighter.”

No matter the stress, Myia and colleagues focus on the bright side, “We always tap each other, you did great, ginalingan mo na naman, after a long shift.”

On the other coin’s side, the silent interplay of the BCPO frontliners always comes around into the perspective as Myia wants it known.

“They, (the Baguio City Police Office) always offer us free ride, going to the hospital and back home, Myia stressed.

If frontliners seem to many, a broken song record harping a same tune grating on nerves, well, all of them would be happiest for being broken song records.

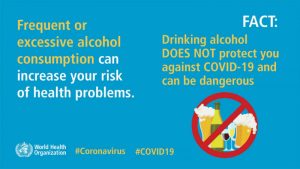

Always, other frontliners and Myia won’t stop advising all and sundry, “All should do a part in minimizing spread of infection, the simple ways to protect yourself and loved ones. Wearing a face mask is caring.”

“Secondly, everyone must comply with the control of movement, practice social distancing and handwashing. Boosting their immune system, eating foods rich in Vitamin C. Let us all help each other; we will win this battle,” Myia exhorted.

Tribe folks of Gonogon, Mountain Province, where Myia traces her roots sure will surely nod their heads approvingly that their daughter braids with the fine threads that keep intact the thin frontliners line.

But the fine braids and strand of the thin frontliners line will eventually fray if discrimination on them keeps recurring, like what happened again, last Tuesday when a nurse working in Manila was evicted from her boarding house after she tested positive of corona.

Dr. Zenaida Beltejar, Philippine Red Cross (PRC) services consultant, cried openly upon seeing the poor nurse who wandered the streets of Quezon City, no one having helped her.

“I cried because that’s not how we should treat a nurse who contracted the virus. How many displaced nurses are out there on the streets?” Beltejar asked, bitterly. Senator Richard Gordon, PRC chair, “This is discrimination. We shouldn’t do this to our fellow Filipinos.”

Indeed, it shouldn’t be, observers agree, else the thin frontliners line could snap – Bony A. Bengwayan

You might also like: